For the past 15 years my work has focused on addressing injustice in black and brown communities. I target issues of structural discrimination, violence, poverty, migration, marginalization and human rights. My work in film and photography has always revolved around what I call the beautiful struggle: life after death, family stories, human resilience and bridging the spaces between these subjects.

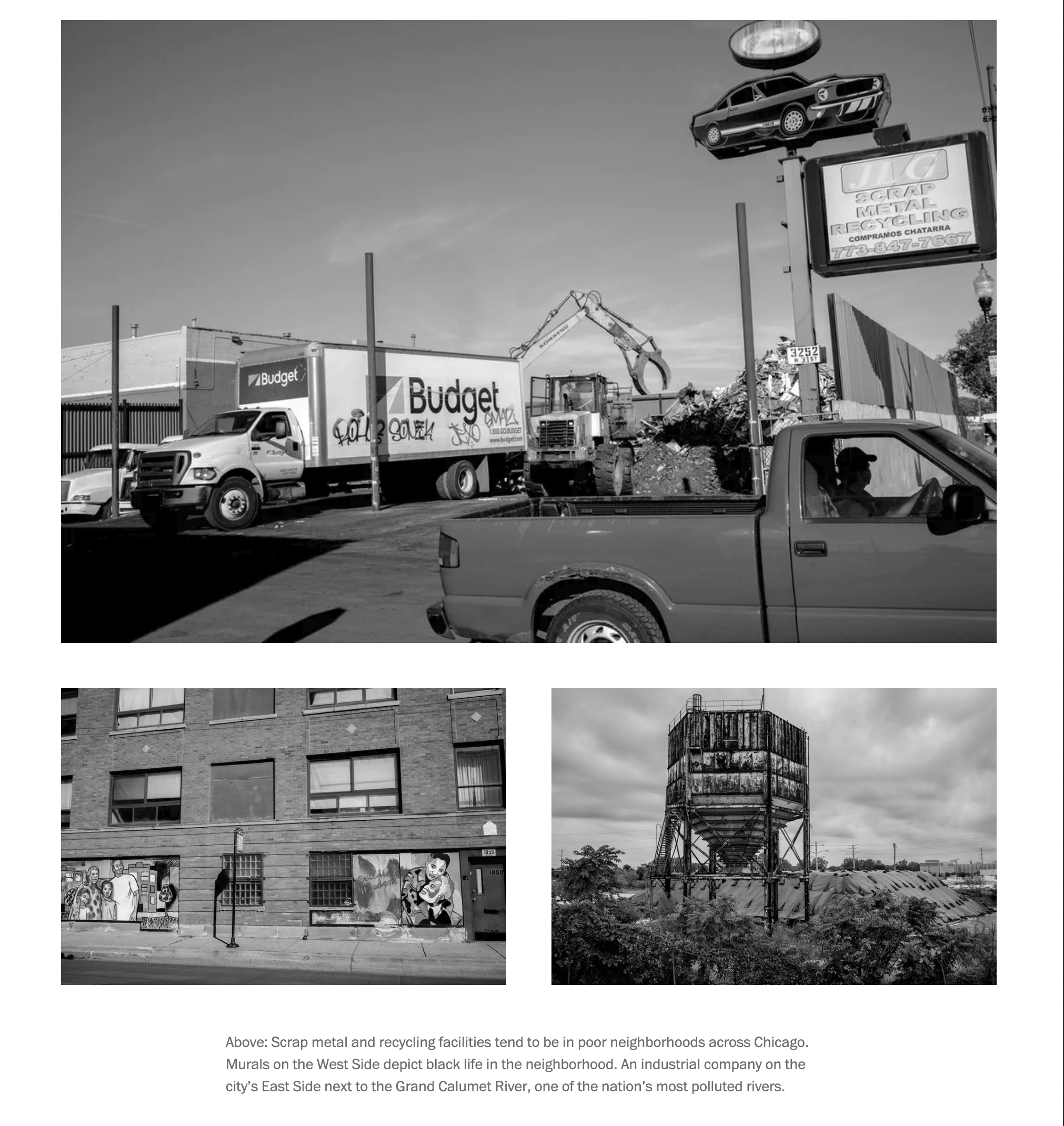

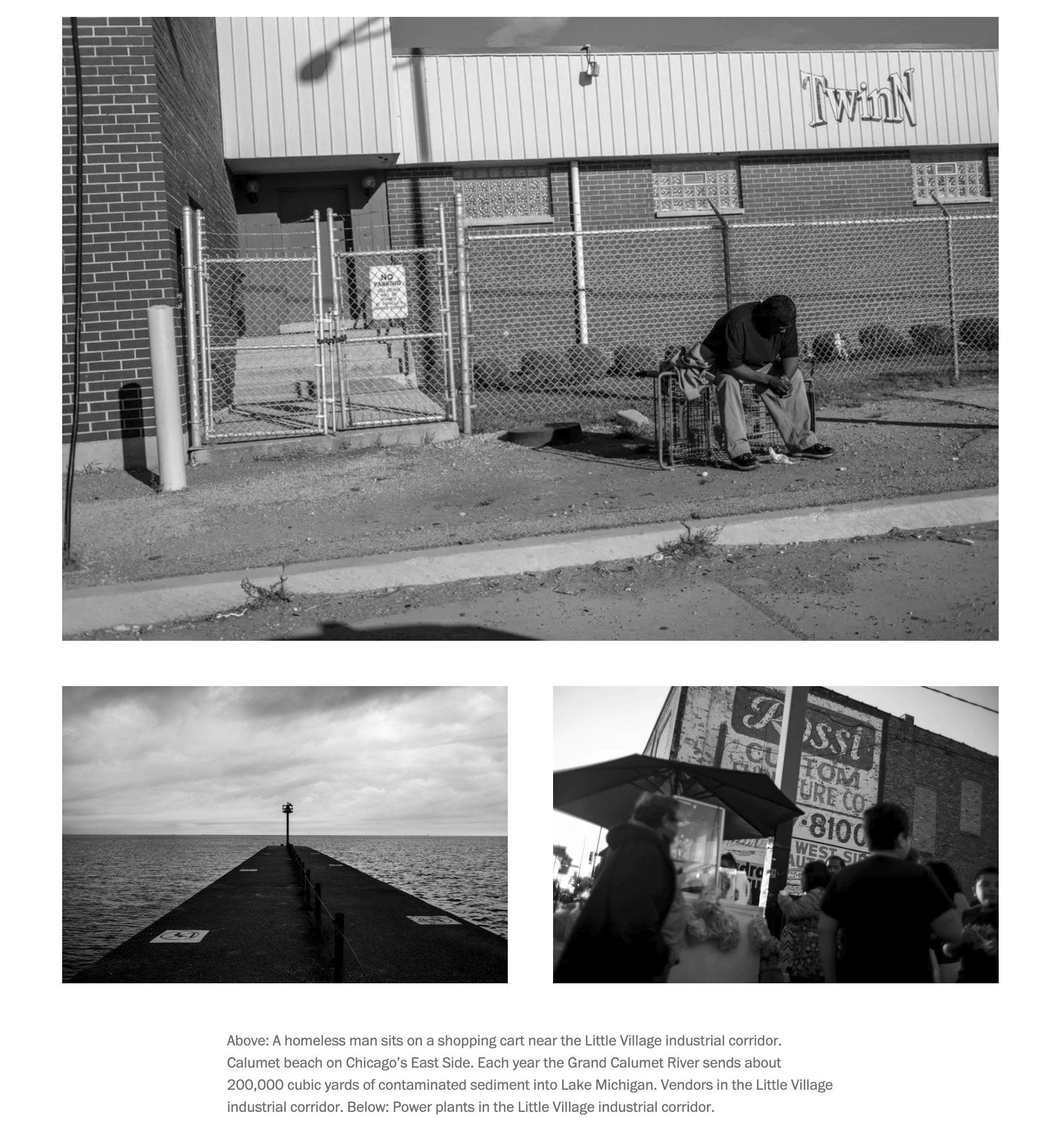

For this issue I was compelled to address the topic of race in a different way and thought about neighborhood effects on people of color, who are the most vulnerable population when it comes to environmental injustice in urban America. Environmental racism begins in the barrios and neighborhoods where black and brown people live, go to school, work and raise their families. In the third largest American city, Chicago’s black and brown people live in some of the most polluted neighborhoods, surrounded by superfund sites, toxic landscapes, illegal dumping and air pollution.

We often don’t correlate racism with polluted neighborhoods in American cities. That seems like something that happens on the other side of the world. But the reality of environmental racism has been rooted in America’s history, in which municipal zoning laws and restrictive policies such as Jim Crow and redlining have locked the poor into toxic neighborhoods — and today not much has changed.

To illustrate the landscape where environmental injustice takes place in contemporary Chicago, I spent most of my time driving in and around black and brown communities: neighborhoods on the South, East and West Side of the city, once populated by European immigrants considered to be the undesirables many years ago. I didn’t have to look hard for the structures polluting our neighborhoods; they tower over us, hiding in plain sight behind schoolyards, between ribbons of concrete highways.

The residents in these neighborhoods have injected their culture and labor to make the city what it is today. Chicago’s politicians need to step up and provide safe neighborhoods, living-wage jobs and excellent public schools with a clean and healthy environment for the people who hold the city on their shoulders.

Carlos Javier Ortiz is a director, cinematographer and documentary photographer who focuses on urban life, gun violence, racism, poverty and marginalized communities. In 2016, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship for film and video, and his work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and the Library of Congress.

A Thousand Midnights was selected for the 2017 PBS online film festival. You can see it here, along with many other cool shorts, beginning July 17! Please mark your calendars, Share with friends and please vote. Thank you all.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this blog post are solely those of the respondents.

Director, Cinematographer and Photographer Carlos Javier Ortiz talks about the choices that went into his emotional narrative of the Great Migration and its effects on the present.

PBS: A Thousand Midnights is filmed entirely in black and white. What was the creative decision behind this?

Carlos Javier Ortiz: My previous film "We All We Got" was filmed in black and white as well. A Thousand Midnights is a part of a trilogy of short films chronicling the contemporary stories of Black Americans who came to the North during the Great Migration. Beginning with my mother-in-law’s story, I’m exploring the legacy of the Great Migration a century after it began. Filming in black and white was a creative decision to make these connections.

Last year, there were 470 homicides and more than 2,900 people shot in Chicago making it the deadliest city in the U.S., this according to the Chicago Tribune. Directed by Carlos Javier Ortiz, the short documentary We All We Got details the impact gun violence has on communities in the city of Chicago and how those involved confront the challenges they face in their lives every day. READ MORE

We All We Got

Opening with the POV of a helicopter surveying the Chicago city streets — and concluding with a final shot of the heavenly clouds above them — We All We Got takes a macroscopic view of the city’s gun violence and youth fatalities within the African-American community. Shot in black-and-white and with minimal connective tissue, this social issue tableau incorporates fragmentary bits of character — a man advocating for peace marching through the streets, a family in shock as the splattered blood of a deceased loved one is washed off the basketball court concrete where it lies — tone poems, and expressionistic photography to create a meditative sense of loss. Anger isn’t the primary emotion behind each protest, but rather a parasitic feeling of sadness. As we hear the damning statistics of modern gun fatalities in Chicago public schools, with parents holding framed photos of their lost loved ones, Carlos Javier Ortiz’s We All We Got proves itself a startling artifact of a community that grieves together, collectively experiencing the pain they can never fully shed.

Siretha White was at her 11th birthday party when she was killed in 2006. Nugget, as she was known to her family, had been celebrating in her cousin’s home when gunman Moses Phillips, who had reportedly been aiming at a man who was on the porch, shot through the front window fatally wounding her as she ran toward the back of the house. It was a sudden, shocking death that devastated the Whites and many others in their neighborhood of Englewood, Chicago. READ MORE

The results of urban violence are pretty much the same the world over: dead young people. Visual journalist Carlos Javier Ortiz has documented the lives of communities caught up in this spiral of violence. Recent work has looked at Chicago, Philadelphia and Guatemala City. Ortiz’s work puts a human face on what can feel like an all too anonymous parade of victims of gun violence. He also examines the hope and resilience in each community. Ortiz joins us to talk about his work. We’ll also hear from Mark Schulte, education director for the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, which is putting on the event that brings Ortiz to Chicago.

(Photo by Carlos Javier Ortiz/Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting)

Siretha White was celebrating her 11th birthday when a stray bullet ripped through the front window of her aunt’s Chicago home, striking the young girl in the head and killing her almost instantly. Eight days earlier, and only a few blocks away, a stray bullet fired from an AK-47 had pierced a basement window and killed 14-year-old Starkeisha Reed. Her family was planning to move out of the house in a few days READ MORE

By David Gonzalez: The killing of a high school honors student and majorette who had participated in President Obama’s inaugural parade earlier this year elicited national outrage. Granted, some people who had been following gun violence against young people in Chicago wondered where the outrage was when other teenage boys were murdered. READ MORE

Guns without Borders in Mexico and Central America March 29 - November 16, 2014

Museums are filled with depictions of violence. Christ on the cross, The Trojan War, saints vanquishing Satan—these are common narratives in paintings lining the halls of most fine art institutions. In the case of arms and armor, these beautiful objects are understandably displayed to emphasize their exquisite craftsmanship, just as they are in Knights! Seen from this perspective, it is easy to romanticize items like swords and shields as hallmarks of a forgotten era of chivalry. However, the Worcester Art Museum presents an alternative narrative, reminding viewers that arms are designed to assault and armor exists to protect our fragile bodies from injury: READ MORE

By James E. Causey: If a picture is worth a thousand words, then Carlos J. Ortiz's camera lens has written an encyclopedia on youth violence.

Through his black and white photography, Ortiz has captured the pain of a mother saying goodbye to her son as he lay in a casket. Her hand gently caresses the top of the teen's head.

In another photo, Ortiz shows a mother collapsing in a heap outside her corner store after hearing that her son had been shot and killed during a robbery. Police are standing around helpless. READ MORE

This video represents the continuation of our Facing Change: Documenting America (FCDA) series. FCDA is a non-profit collective of prominent photographers and writers who have come together to explore the United States during one of the most enduring times in the nation’s history.

The work of Carlos Javier Ortiz, one of the FCDA photographers, sheds light on the crime in Chicago and migrant workers in Illinois. READ MORE